Planes, trains, automobiles - Thomas Bayrle - Interview

ArtForum, Summer, 2002 by Kasper Konig, Thomas Bayrle, Daniel Birnbaum

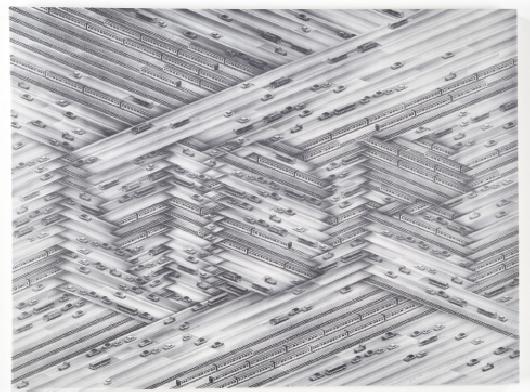

WITH A SPATE OF RECENT EXHIBITIONS AND THE SHOWCASING of his huge image of an airplane, Flugzeug, 1984, at the reopened Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Thomas Bayrle`s audience may at last be catching up with the Frankfurt-based artist. One ally, however, seems to have been onto Bayrle from the start: Ludwig director Kasper Konig, an abiding admirer who included Flugzeug in his pivotal 1984 survey of contemporary German art, "von hier aus" (From here out). As Konig has long observed and today`s viewers are now discovering, the roots of Bayrle`s graphics and experimental printing lie in German Pop, but his interest in art`s relation to society has opened up original investigations in which cybernetics and even biology play a part. What emerges are visually perplexing, riveting patterns, drawing on aspects of urbanism, pornography, nanotechnology, and the world of mass-produced commodities. In a catalogue for a 1997 exhibition in Japan, where Bayrle`s work has received more attention than in his native Germany, he st ates, "I consider the relationship between individual and collective/community the same as that between dot and grid, the dot representing a component of the grid, and between cell and body, the cell being its basic element." The principle at work--the blending of heterogeneous elements into Piranesi--esque visual patterns-has been central to Bayrle`s art since his early political paintings of the `60s. In Mao, 1966, an automatic painting on wood (outfitted with an engine), party members are slowly transformed into a Maoist star and then into the face of Chairman Mao himself. The problem was, Bayrle put neckties on his Chinese Communists, a decision so reactionary that the young artist--Joseph Beuys used to call him "the guy with the machines"--was denied entry to the party when he tried to join. Who said political art was easy?

More and more viewers are fascinated by Bayrle`s perplexing investigations into the infrastructure of our visual surroundings. Although Bayrle is becoming better appreciated for his work, he`s been at the epicenter of a network of creative connections across generations and geographies for three decades. Not all great artists are interested in teaching, and it`s even rarer that they`re good at it. But it does happen, and Bayrle is a case in point: The artist`s tenure at the Stadelschule has made him a key figure in European art. Now in his mid-sixties, he has given younger colleagues like Martin Kippenberger and Andreas Slominski the chance to teach, and some of his recent students, such as Tobias Rehberger, are stars in the gallery and museum world. On any given day you may find Bayrle designing a book for Philip Johnson, cooking stinging-nettle soup with Rirkrit Tiravanija, or producing new work for shows in Germany or Japan.

We asked Konig to sit down with Bayrle to talk about his work as an artist and teacher. They met up in front of the massive Flugzeug, a work that has taken on new layers of meaning after the events of 9/11.

KASPER KONIG: In 1984 we included Rugzeug in the exhibition "von hier aus." It hasn`t been shown since then?

THOMAS BAYRLE: The sixty-two parts that make up the whole work were packed away somewhere in a box. Strangely enough, I happened to pull them out again on 9/II. I had hung up about half of the strips on the wall when I heard somebody call me from the balcony: "Something terrible has happened! A plane has crashed into the World Trade Center." I stopped what I was doing immediately, and rather than sit down in front of the television, I walked down to the Rhine.

KK: What prompted you to make such a huge cloth of cut-up photos in the first place?

TB: Since the early `60s I`ve been interested in the idiotic, absurd, grotesque images of mass production and consumption. In addition to coffee cups, oxen, cars, and telephones, I`ve used airplanes as components within a larger compilation of parts. For instance, in 1980 I made a silk-screen print for Lufthansa called Flugzeug aus Flugzeugen [Plane of planes]. The big plane comprised 760 smaller planes against a background of a sky filled with tinier planes. I liked the big plane and thought it was funny. But two years later, I wanted to see the other side of the coin.

KK: And what was your Intention--was Flugzeug the more serious side of this?

TB: This work was about the futility of trying to find an image that stands for an entire system. About a solution--both in terms of material and content--that can show the real madness of it all clearly for at least five minutes. I used the 1980 "nice plane" as a module again . . . and increased the number of planes from two thousand to one million.

KK: Was that supposed to generally symbolize one aspect of civilization?

TB: Yes. From jobs to hospitals, airlines, insurance companies, and market speculation. At the time, I wanted to use an apocalyptic sign to stand for civilization. I wanted to create a gray mass of photos to stand for the takeoffs, landings, reservations, cancellations, gallons and gallons of gasoline. Pure quantity as quality, that`s what I wanted to see.

KK: What was your technique?

TB: Using a platen press in a printer`s shop, I printed the plane module with the two thousand smaller planes on large rubber cloths. Then, with the help of my family, in a different location, I distorted, photographed, and developed the rubber images. At a third place I assembled the photos of different parts of the big plane. I worked on the details in a deliberately distant manner, without having an overview of the whole thing, without seeing it in its entirety as I was working. It wasn`t until the end that all the parts I had created were assembled in a large hall. This method seemed to correlate to working in a factory--an activity I was competing with on a psychological level, so to speak.

KK: How does this attention to detail affect your artwork?

TB: When I concentrate on a detail, the entire work becomes recharged, as if it were being poured from a mold of its total form. Since the whole is found in each part and vice versa, I project the parts onto one another. The areas where the parts come together in the montage create little fractures that are important to me. If I were to interpret these fractures in my view as conflicting social customs or diverging individualities, then they--in their variety--could stand for material wealth or the potential for conflict.

KK: What role does having an overview play for you?

TB: I have my doubts about "strategic plans." That attitude has almost always been abused by those with political power. What I am interested in is working very closely on parts of the whole, on the details. The constant "being on the go" attitude-driving down the highway at any time day or night ... insurance companies ... money transactions-we no longer have an overview of the whole. For me, a view of something in its entirety comes from the details, in the overlap of details-from the bottom up.

KK: Where did this perspective come from?

TB: From weaving. I look at fabric for its threads-threads that crisscross and intersect constitute the fabric or material as a whole. Within this context, the thread stands for the individual. The sum of all the parts-the threads-is the material, or the collective.

KK: Early in your career you worked as a jacquard weaver with the Mikro Makro company. How did this experience affect your work? Fabric is flat; how do you develop your three-dimensional cities out of the surface?

TB: Combined with my experience as a typesetter, the work in the weaving mill gave me the decisive impetus to see artistic processes and to move material according to my own vision. By elevating or sinking the threads of a fabric`s surface, I can produce a three-dimensional space as a weave or a relief. Into these tiny containers of ups and downs I can nest houses, streets, apartments, wonderfully monotonous cities. The overpasses and underpasses in Tokyo, for example, were like segments of a fabric`s connective tissue magnified to a giant scale.

KK: Whenever I`ve traveled to Japan I`ve repeatedly thought of your method in order to understand a culture that has become increasingly incomprehensible to me. I understand why you are much better known as an artist there than you are here.

TB: In 1977 I spent the first six weeks of the summer in Tokyo. In the August heat the life on the street appeared fluid and interconnected to me-digital, monumental. From the pores to the traffic-ying and yang, stop and go, two thousand people crossing a road to the dingdong of the traffic monitor.

KK: Are there other areas that have influenced your microworld?

TB: Brain researcher Wolf Singer has taught us that there is no real supervisor within the brain, no static center that controls everything. Rather, depending on the situation, spontaneous connections or constellations develop because of the various formations of cells. I think of these constellations-which prompt innumerable, individual actions and reactions-as a kind of "microdemocracy."

KK: Do you transfer the microdemocracy concept to yourself and your environment?

TB: At times, during a cold rain shower I have felt like a lump consisting of millions of cells-or like the band Devo, presenting itself as a single individual constructed from several members.

KK: Is this view connected to your role as a teacher?

TB: With time I expanded my personal construct to include the individuals in my class. Since I myself was "made up of parts," I could extend the "building kit" over the existences surrounding me. There was the possibility of incorporating parts of the students` problems into myself and vice versa-organizing classes as a kind of "washing machine," a hump yard of fragments.

KK: In other words, you made a connection among woven fabrics, cell structures, and social frameworks?

TB: In 1968 I created a work made of 576 pairs of shoes that showed a man eating a sandwich. For my work of a woman drinking coffee, I needed 1,404 cups. No more and no less! Perhaps in a rather impermissible way I shift back and forth between areas of knowledge or social/physical conglomerations that are distinct. I have always integrated subinformation into my "compilations" and have "swerved around the bend," formally speaking. In other words, CupCupSupercup is still my preferred mode of getting around.

Kasper Konig is director of the Museum Ludwig, Cologne. (See Contributors.)

Translated from German by Louisa Schaefer.

Thomas Bayrie, CAPSEL (detail), 1983, photocollage on paper, 20 x 283/4".

KASPER KONIG, director of the Museum Ludwig, Cologne, was rector of the Frankfurt Stadelschule from 1987 to 2000 and founding director of its renowned Portikus gallery. Konig established his curatorial reputation with the Munster Sculpture Project, a decadal event that debuted in 1977, and the now legendary shows "Westkunst," in Cologne in 1981, and "von hier aus" (From here out), in Dusseldorf in 1984. This summer Konig brings Matthew Barney`s "CREMASTER Cycle" to the Museum Ludwig, where it begins its world tour. In these pages Konig talks with Thomas Bayrle, an artist he has admired since the early `80s and an influential teacher at the Stadelschule, whose work is currently meeting with renewed interest in his native Germany. PHOTO: ROMAN MENSING

Thomas Bayrle, Autobahnkopf, 1988/89, 9:21

Thomas Bayrle, Gummibaum, 1993, 8:22

Thomas Bayrle, Dolly Animation, 1998, 5:44

Thomas Bayrle, B(Alt), 1997, 2:13

Thomas Bayrle, Sunbeam, 1993/94, 11:01

Thomas Bayrle

1937 born in Berlin

lives and works in Frankfurt/Main

Solo exhibitions (selection)

2007

Galerie Barbara Weiss, (with Monika Baer)

Thomas Bayrle, FRAC Limousin, Limoges

Thomas Bayrle, Office for Contemporary Art, Oslo

Thomas Bayrle, Jacke wie Hose, Galerie Johann Widauer, Innsbruck

2006

Thomas Bayrle, 40 Jahre Chinese Rock ´N´Roll,

Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main

Thomas Bayrle. Happy Days Are Here Again, Gavin Brown Enterprises, New York

2005

Cubitt Gallery, London

2004

Thomas Bayrle: Carlos, Oldenburger Kunstverein

2003

Autostrada, Galerie Barbara Weiss

Eiserner Vorhang/Safety Curtain. A project of museum in progress in co-operation with the Vienna State Opera

2002

Thomas Bayrle, Grazer Kunstverein

Thomas Bayrle, Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt

2001

Kartoffelzähler, JohannWidauer, Innsbruck

Thomas Bayrle. Bilder, Zeichnungen, Druckgrafik aus den Jahren 1967 bis 2001, Galerie Meyer-Ellinger, Frankfurt

Layout, CCA, Kitakyushu

2000

flying home..., Museum in Progress, Vienna

Philip Johnson, 1999 und Werke von 1967 - 2000, Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin

1998

Galerie Meyer-Ellinger, Frankfurt

Dolly Animation,Galerie Francesca Pia, Bern

1997

Koriyama City Art Museum, Koriyama

Academy of Art & Design, Beijing

TassenTassen, Museum Moderner Kunst, Frankfurt

1996

Kunsthalle St. Gallen

1995

Galerie Meyer-Ellinger, Frankfurt

1994

Film Video Materialien, Portikus, Frankfurt

1990

Autobahnkopf, Portikus, Frankfurt

1989

Pinsel durchgespielt, Kunstverein Freiburg

Thomas Bayrle 1983 - 88, Seed Hall, Tokyo

1988

Madonna Jaguar, Kunsthalle Innsbruck

1987

Thomas Bayrle 1967 und 1987, Frankfurter Kunstverein

1986

GOLF, Auto Museum, Wolfsburg

1984

Capsel, Museum am Ostwall, Dortmund

1983

Druckgrafik 1960-83, Städtische Galerie, Wolfsburg

1980

Rasterfahndung, Goethe-Institut, San Francisco

Graphic Gathering, Stanford University, Palo Alto

1977

Cities and Accumulations, WAKO, Tokyo

1972

Formation Serielle, La Pochade, Paris

Kiko Galleries, Houston

1971

Studio S, Rome

1968

Mäntel - Tragbare Grafik, Art Intermedia, Cologne

produzione Bayrle,Galleria Apollinaire, Milan

1965

Galerie Buchholz, Munich

1964

Städtisches Museum, Göttingen

1963

DRUCK, Galerie Bergsträsser, Darmstadt

Group exhibitions (selection)

2007

Das Kapital-Blue Chips und Masterpieces, Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt/M

What does the jellyfish want?, Museum Ludwig, Cologne

Lyon Biennial

Whenever It Starts It Is the Right Time, Frankfurter Kunstverein

Thomas Bayrle, screening of Sunbeam, Superstars, Autobahn-Kopf, Office for Contemporary Art Norway, Oslo

Screening of Sunbeam, Autobahnkopf, Select: A Night with Rosalind Nashashibi, Tate Modern, London

Imagery Play, PKM Gallery, Beijing

2006

Piktogramme - die Einsamkeit der Zeichen, Kunstmuseum Stuttgart

Dark Places, Santa Monica Museum of Art, Santa Monica

Summer in Love, Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt

Informal City, Beijing Case, Zero-Field,

ZKM, Museum für Neue Kunst, Karlsruhe

4. Berlin Biennale für zeitgenössische Kunst: OF Mice and Men, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin

The 6th Gwangju Biennale, South Korea

totalstadt.beijing case, ZKM, Museum für Moderne Kunst, Karlsruhe

Choosing My Religion, Kunstmuseum Thun, Thun

The Expanded Eye, Kunsthaus Zürich, Zurich

2005

Archive in motion, 50 years Documenta, Fridericianum, Kassel

Automobilisé, Galerie Ilka Bree, Bordeaux

Zur Vorstellung des Terrors: Die RAF. Ausstellung, Kunst-Werke, Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin

Summer in love, Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt

2004

Berlin-Moskau / Moskau-Berlin 1950-2000, Staatliche Tretjakow-Galerie, Moskow

Pop Cars. Amerika-Europa, Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg

9. Triennale Kleinplastik Fellbach, Alte Kelter, Fellbach

Deutschland sucht, Kölnischer Kunstverein

Grey Goo, Flaca, London

Cupcup and the happy Medium, Dowse-Museum, Wellington, New Zealand

Utopia Station, Haus der Kunst, Munich

2003

Bayrle, Greenfort, Zybach, Galerie Francesca Pia, Bern

Nation, Frankfurter Kunstverein

50. Biennale di Venezia

Berlin-Moskau / Moskau-Berlin 1950-2000, Martin-Gropius Bau, Berlin

Klosterfelde Invite #8, Klosterfelde, Berlin

2002

Europaweit - Kunst der 60er Jahre, Städtische Galerie, Karlsruhe

2001

Frankfurter Kreuz. Transformationen des Alltäglichen in der zeitgenössischen Kunst, Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt

DC: Thomas Bayrle/ Bodys Isek Kingelez, Museum Ludwig, Cologne

2000

Floating Cities. Die europäische Stadt in Bewegung, conference (06-22 - 06-25-2000) Guardini Stiftung e.V. in the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin

out of space, Schnitt Ausstellungsraum zu Gast im Kölnischen Kunstverein, Cologne

1999

Serien/ Konzepte in Foto/ Video, Museum Ludwig, Cologne

1998

Technoculture FRI ART, Centre Contemporaine, Friburg

Life Style, Kunsthaus Bregenz

Anticipation, Centre pour l'image Contemporaine, Genf

Massornament, Kunsthallen Brandts Klaedefabrik, Odense

... mit Studenten, Shift, Berlin

Die Macht des Alters, Deutsches Historisches Museum, Kronprinzenpalais, Berlin

1997

Urban Space, de Singel, Antwerp

KünstlerInnen, Museum in Progress, Kunsthaus Bregenz

1996

Grafik, Galerie Klosterfelde, Berlin

L'Art de Plastique, Ecole de Beaux Arts, Paris

1995

Elastic Lights, Sidney Gallery

Prix Ars Electronica, Linz

1993

Neue Kunst in Hamburg, Kunstverein Hamburg

Ars Electronica, Linz

Compkuenstlerg, Künstlerwerkstatt Lothringer Straße, Munich

1989

On Kawara - Wieder und Wieder, Portikus, Frankfurt

Ars Electronica, Linz

1985

IBA, Berlin, Milan

Deutsche Graphiker, Gummersons, Stockholm

1984

Orwell, Museum des 20. Jahrhunderts, Vienna

1983

Utopian Visions in Modern Art, Hirshhorn Museum , Washington

1977

documenta 6, Kassel

1975

Der Einzelne und die Masse, Kunsthalle Recklinghausen

1971

Graphik der Welt, Kunsthalle Nürnberg

Contemporary Graphic, Oxford Gallery, London

Kunst und Politik, Frankfurter Kunstverein

1970

Konzepte einer neuen Kunst, Göttinger Kunstverein

Sammlung Feelisch, Museum am Ostwall, Dortmund

Kunst und Politik, Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe

1969

Industrie und Technik in der deutschen Malerei, Lehmbruck-Museum, Duisburg

1968

British International Print Biennale, Bradford

Kunst-Stoffe, Art Intermedia, Cologne

1967

Serielle Formationen, Studio Galerie, Universität Frankfurt

1966

EXTRA, Museum Wiesbaden

1965

Between poetry and painting, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London

1964

documenta 3, Kassel

1963

Schrift und Bild, Kunsthalle Baden-Baden und Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

1937 born in Berlin

lives and works in Frankfurt/Main

Solo exhibitions (selection)

2007

Galerie Barbara Weiss, (with Monika Baer)

Thomas Bayrle, FRAC Limousin, Limoges

Thomas Bayrle, Office for Contemporary Art, Oslo

Thomas Bayrle, Jacke wie Hose, Galerie Johann Widauer, Innsbruck

2006

Thomas Bayrle, 40 Jahre Chinese Rock ´N´Roll,

Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main

Thomas Bayrle. Happy Days Are Here Again, Gavin Brown Enterprises, New York

2005

Cubitt Gallery, London

2004

Thomas Bayrle: Carlos, Oldenburger Kunstverein

2003

Autostrada, Galerie Barbara Weiss

Eiserner Vorhang/Safety Curtain. A project of museum in progress in co-operation with the Vienna State Opera

2002

Thomas Bayrle, Grazer Kunstverein

Thomas Bayrle, Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt

2001

Kartoffelzähler, JohannWidauer, Innsbruck

Thomas Bayrle. Bilder, Zeichnungen, Druckgrafik aus den Jahren 1967 bis 2001, Galerie Meyer-Ellinger, Frankfurt

Layout, CCA, Kitakyushu

2000

flying home..., Museum in Progress, Vienna

Philip Johnson, 1999 und Werke von 1967 - 2000, Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin

1998

Galerie Meyer-Ellinger, Frankfurt

Dolly Animation,Galerie Francesca Pia, Bern

1997

Koriyama City Art Museum, Koriyama

Academy of Art & Design, Beijing

TassenTassen, Museum Moderner Kunst, Frankfurt

1996

Kunsthalle St. Gallen

1995

Galerie Meyer-Ellinger, Frankfurt

1994

Film Video Materialien, Portikus, Frankfurt

1990

Autobahnkopf, Portikus, Frankfurt

1989

Pinsel durchgespielt, Kunstverein Freiburg

Thomas Bayrle 1983 - 88, Seed Hall, Tokyo

1988

Madonna Jaguar, Kunsthalle Innsbruck

1987

Thomas Bayrle 1967 und 1987, Frankfurter Kunstverein

1986

GOLF, Auto Museum, Wolfsburg

1984

Capsel, Museum am Ostwall, Dortmund

1983

Druckgrafik 1960-83, Städtische Galerie, Wolfsburg

1980

Rasterfahndung, Goethe-Institut, San Francisco

Graphic Gathering, Stanford University, Palo Alto

1977

Cities and Accumulations, WAKO, Tokyo

1972

Formation Serielle, La Pochade, Paris

Kiko Galleries, Houston

1971

Studio S, Rome

1968

Mäntel - Tragbare Grafik, Art Intermedia, Cologne

produzione Bayrle,Galleria Apollinaire, Milan

1965

Galerie Buchholz, Munich

1964

Städtisches Museum, Göttingen

1963

DRUCK, Galerie Bergsträsser, Darmstadt

Group exhibitions (selection)

2007

Das Kapital-Blue Chips und Masterpieces, Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt/M

What does the jellyfish want?, Museum Ludwig, Cologne

Lyon Biennial

Whenever It Starts It Is the Right Time, Frankfurter Kunstverein

Thomas Bayrle, screening of Sunbeam, Superstars, Autobahn-Kopf, Office for Contemporary Art Norway, Oslo

Screening of Sunbeam, Autobahnkopf, Select: A Night with Rosalind Nashashibi, Tate Modern, London

Imagery Play, PKM Gallery, Beijing

2006

Piktogramme - die Einsamkeit der Zeichen, Kunstmuseum Stuttgart

Dark Places, Santa Monica Museum of Art, Santa Monica

Summer in Love, Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt

Informal City, Beijing Case, Zero-Field,

ZKM, Museum für Neue Kunst, Karlsruhe

4. Berlin Biennale für zeitgenössische Kunst: OF Mice and Men, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin

The 6th Gwangju Biennale, South Korea

totalstadt.beijing case, ZKM, Museum für Moderne Kunst, Karlsruhe

Choosing My Religion, Kunstmuseum Thun, Thun

The Expanded Eye, Kunsthaus Zürich, Zurich

2005

Archive in motion, 50 years Documenta, Fridericianum, Kassel

Automobilisé, Galerie Ilka Bree, Bordeaux

Zur Vorstellung des Terrors: Die RAF. Ausstellung, Kunst-Werke, Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin

Summer in love, Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt

2004

Berlin-Moskau / Moskau-Berlin 1950-2000, Staatliche Tretjakow-Galerie, Moskow

Pop Cars. Amerika-Europa, Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg

9. Triennale Kleinplastik Fellbach, Alte Kelter, Fellbach

Deutschland sucht, Kölnischer Kunstverein

Grey Goo, Flaca, London

Cupcup and the happy Medium, Dowse-Museum, Wellington, New Zealand

Utopia Station, Haus der Kunst, Munich

2003

Bayrle, Greenfort, Zybach, Galerie Francesca Pia, Bern

Nation, Frankfurter Kunstverein

50. Biennale di Venezia

Berlin-Moskau / Moskau-Berlin 1950-2000, Martin-Gropius Bau, Berlin

Klosterfelde Invite #8, Klosterfelde, Berlin

2002

Europaweit - Kunst der 60er Jahre, Städtische Galerie, Karlsruhe

2001

Frankfurter Kreuz. Transformationen des Alltäglichen in der zeitgenössischen Kunst, Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt

DC: Thomas Bayrle/ Bodys Isek Kingelez, Museum Ludwig, Cologne

2000

Floating Cities. Die europäische Stadt in Bewegung, conference (06-22 - 06-25-2000) Guardini Stiftung e.V. in the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin

out of space, Schnitt Ausstellungsraum zu Gast im Kölnischen Kunstverein, Cologne

1999

Serien/ Konzepte in Foto/ Video, Museum Ludwig, Cologne

1998

Technoculture FRI ART, Centre Contemporaine, Friburg

Life Style, Kunsthaus Bregenz

Anticipation, Centre pour l'image Contemporaine, Genf

Massornament, Kunsthallen Brandts Klaedefabrik, Odense

... mit Studenten, Shift, Berlin

Die Macht des Alters, Deutsches Historisches Museum, Kronprinzenpalais, Berlin

1997

Urban Space, de Singel, Antwerp

KünstlerInnen, Museum in Progress, Kunsthaus Bregenz

1996

Grafik, Galerie Klosterfelde, Berlin

L'Art de Plastique, Ecole de Beaux Arts, Paris

1995

Elastic Lights, Sidney Gallery

Prix Ars Electronica, Linz

1993

Neue Kunst in Hamburg, Kunstverein Hamburg

Ars Electronica, Linz

Compkuenstlerg, Künstlerwerkstatt Lothringer Straße, Munich

1989

On Kawara - Wieder und Wieder, Portikus, Frankfurt

Ars Electronica, Linz

1985

IBA, Berlin, Milan

Deutsche Graphiker, Gummersons, Stockholm

1984

Orwell, Museum des 20. Jahrhunderts, Vienna

1983

Utopian Visions in Modern Art, Hirshhorn Museum , Washington

1977

documenta 6, Kassel

1975

Der Einzelne und die Masse, Kunsthalle Recklinghausen

1971

Graphik der Welt, Kunsthalle Nürnberg

Contemporary Graphic, Oxford Gallery, London

Kunst und Politik, Frankfurter Kunstverein

1970

Konzepte einer neuen Kunst, Göttinger Kunstverein

Sammlung Feelisch, Museum am Ostwall, Dortmund

Kunst und Politik, Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe

1969

Industrie und Technik in der deutschen Malerei, Lehmbruck-Museum, Duisburg

1968

British International Print Biennale, Bradford

Kunst-Stoffe, Art Intermedia, Cologne

1967

Serielle Formationen, Studio Galerie, Universität Frankfurt

1966

EXTRA, Museum Wiesbaden

1965

Between poetry and painting, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London

1964

documenta 3, Kassel

1963

Schrift und Bild, Kunsthalle Baden-Baden und Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam